When my investigations began into the life

of Theodore H. White, as revealed in my last post on his eponymous

College of Science, I had nearly forgotten an important discovery

that was thankfully still waiting for me after quite a long wait. When

I had first stumbled upon the newspaper account of TH White's trial,

I had also discovered the whereabouts of a lone surviving copy of his

College of Science's “Red Book” on the digital shelves of New

England's Uncommon Books. The price was too high for a casual purchase and its significance and

rarity not yet realized, so I added it to my shopping cart simply

for future reference. Imagine my surprise when, upon realizing its

importance, and that no archives or libraries held an extant copy,

that there it still remained. So, I was able to come to a reasonable

agreement with the very friendly Tom, owner of Uncommon Books, to acquire the volume, and it arrived yesterday.

|

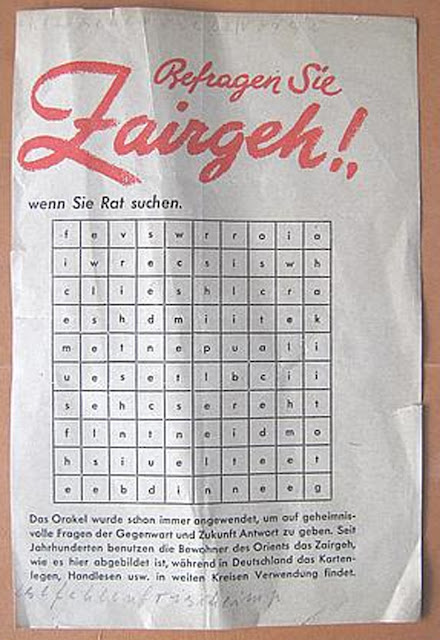

| Dr. White's College of Science "Red Book" |

The Red Book is everything expected and

predicted, and it is simply amazing. Physically, it is an imposing

tome, softcover in cardboard wraps, but measuring some 11”x15”

inches. The red cover which gave the book its nickname during White's

trial is heavily illustrated, with an assortment of esoteric

scenes—clouds of spirit figures, snakes, owls, frogs and other

familiar creatures, dancing skeletons, and orbiting planets—all

nestled among scenes of occult professionals at work performing acts

of mesmerism and healing.

The back cover displays a strange,

wild-eyed occultist visible from the smoky discharge of an oil lamps,

thrusting his hand forth as if to hypnotize the viewer. At 208 pages,

the book is hefty and thick, and literally stuffed-fit-to-bursting

with all manner of esoteric subjects. I'm not ready to draw too many

conclusions about the book's larger place in the world at the time, or what it reveals in the grander scheme of my compatriot's research, but rather want to give an overview for my excited

collaborators in the absence of the ability to provide a pdf just yet

(as the item is far too large for my scanner.) So, let's peel back

its brittle covers and see what secrets await inside!

The frontpiece gives a thorough

breakdown of the book's subjects in the absence of a table of

contents, listing it as a correspondence course in “Spiritualism,

Hypnotism, Personal Magnetism, Mental Healing, Magnetic Healing,

Planetary Readings, and White and Black Art,” before redundantly

repeating these exact same subjects as Professor White's

stock-in-trade for “over twenty years if practical experience.” A

two-page spread follows, showing Drs. Theodore and Cornelia White

illustrated as occult masters: TH White as an Egyptian pharoah

surrounded by spirit guides, seated on a throne with a massive book

of knowledge spread before him, and Cornelia in a scene befitting the

Oracle at Delphi, being fanned by a servant as she consults

the smoke of incense issuing forth from a W-embossed stand. Such illustrations, by either Willard

T. Barnes or Louis F. Kramer, would come back to haunt White in his

trial, when the artist testified that the scenes were not realistic

depictions. According to them, they'd apparently not actually Dr. White drawn from his real life as a spirit-summoning Egyptian pharaoh, and thus damning. Who would have thought?

Proceeding

through the book's opening chapters and introductions, what struck me

most was the overt Christianity present in the work. From the get-go,

the course immediately states, among the promises of “higher

learning” in the Black Arts, its roots in “God-like principles.”

Its opening passages connect all the various disciplines in the book,

then guides students toward the “Student's Prayer” which seems a

typical, if lengthy, Protestant invocation of Jesus' name. The prayer

shows up again and again within the book, used as it is as an

invocation both before and after any exercises presented in the

course. Given its length, there is even some unintentional humor

invoked it later chapters, as the authors recognize that not all

students will be able to memorize the entire text of the lengthy

prayer, and, as much of the work in the first course on spirit

summoning takes place in the dark, there are appeals by the writer

for the student to seek the candlelight of a nearby room to complete

the prayer by reading it aloud if they are unable to commit it to

memory.The scene of an aspiring student stumbling over their prayers in anticipation of deliverance of the book's promises is cringe-worthy, to say the least.

The

first and most lengthy course concerns Spiritualism—more

specifically spirit-summoning, and perhaps more appropriately with a lower-case "s". Dr. White is great at tying together

the miasma of disciplines within his course, informing his students

how their spirit guide is determined by the astrology of their birth

planet (Course F), and how exercises in self-healing can help calm

the mind (Course C). Otherwise, this chapter continues with its

invocations of Christ and lessons on “Entering Into the Silence”

in order to summon spirit guides and other incorporeal entities.

White

goes into a fairly exhaustive breakdown of different types of

mediumship, and sets up a series of tests for students to unlock

their hidden talents. One important aspect of these tests is rubber

insulation for the séance sitters. In fact, a student's neglect of

this important step was White's go-to excuse when refunds were

demanded after a custom...errr...student, failed to summon spirits

under his remote tutelage. Instructions for table tipping and the

construction of personal cabinets follow, with detailed accounts of

prayers and invocations one would be hard-pressed to perform in the

low light the lessons demand. Again, the appeals to God and Christ

are at once striking and expected, given greater Spiritualism's

non-denominational tone, but White's reliance on Christian theology,

and, in particular, First Corinthians, Chapter 12 is still surprising

given the later lessons the book imparts.

|

| Student at Work Developing Mediumship. Note rubber "insulators." |

The

chapter follows with lessons in spirit rapping and alphabet calling,

descriptions and theology of the “Spirit Land,” the meaning of

visions one might receive while in spirit communion (the Eye, the

Cross, the Sword, the Anchor, etc), and, finally, the admonishment we

expected to see from trial accounts—an ALL CAPS appeal to not

allow anyone else, under any circumstances, to touch your personal

copy of the correspondence course, for it “HAS AN ABSOLUTE

TENDENCY TO DESTROY PORTIONS OF THE MAGNETIC FORCES” personalized

for the student by Dr. White when they ordered the course. They'll have to get their own, the doctor reasons.

The

chapter closes with lessons in clairvoyant sleep, materlization

(oddly from the perspective outside

the cabinet, rather than instruting the student on what they should

be accomplishing *inside* the cabinet), automatic writing,

psychometry (including the diagnosis of illness of remote subjects

through a lock of their hair), clairvoyance, and thought

transference—still all under the banner of “Spiritualism.” In

an interesting footnote at the chapter's conclusion, an offer is made

to aspiring clairvoyants that if they can write Dr. White and

accurately describe the contents and descriptions of the College of

Science's offices, they will receive a free diploma. A one dollar

value!

|

| "Now, young Skywalker, you...will...die. *Force lightning!*" |

“Series

B” consists of the course's lessons on Hypnotism, or “Willism” (as opposed to Mesmerism, of "Selfism")

This chapter presents several psychosomatic “tests” not uncommon

in today's “magnetic balance bracelet” trade, an includes proper

instructions of the all-important hand sign of arched thumb and

forefinger to form a horseshoe magnet shape. This chapter is perhaps

the most rife with photographs, all showing Theodore and Cornelia in

various garb (alternating between esoteric robes and fashionable

suits of the era) inducing hypnotic states on subjects both seated

and standing, typically intended to show them influencing the more

simple muscular movements of patients by causing them to lean or rise

from their seats.

|

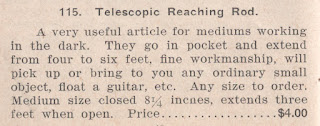

| Aversion to the bottle |

|

| The hat pin through the cheek. |

The lesson quickly moves toward more serious treatments

of alcoholism and cigarettes, inducing healing trances, creating

hallucinations, and, in the penultimate lesson, shoving a hat pin

through a subject's cheek. This, of course, was a serious discussion

throughout the trial, and the doctored photograph revealed by

photographer Louis F. Kramer to have been faked is present, with

some obvious negative-doctoring marks.

Series

C is Dr. White's course on Personal Magnetism, or, as the chapter's

opening illustration shows, the heightened charisma of the self. In

the common nomenclature of the period, the body is likened to a

“personal storage battery,” and the lessons run the gamut of

tricks from influencing rowdy children, attracting or repelling

others, “directing men according to your willpower,” and

self-development.

The

first three chapters constitute White's introduction, and as Series C

closes, White induces the student to “take up the deeper studies in

Occult Science.” These “deeper studies” (as if hypnotizing

others to do your bidding and summoning spirits to reveal the future

wasn't deep enough) includes the next chapter: Series D: “Mental

Healing.” This chapter is more like an extension of the previous

two courses, overlaying their lessons of suggestions and mesmerism to

invoke change in a subject's mental state—most predominantly as it

pertains to their physical health. This includes the basic lessons of

telepathy to establish these rapports, and moves on to thought

transference, diagnosis of diseases, changing the flow of a subject's

magnetism, and exercises to bolster this healing.

Series

E, or Magnetic Healing, takes these concepts a step further, but are

physically, rather than telepathically, induced. Unlike other

chapters, this begins with a testimonial by one Mary Seidel of

Towson, Maryland, who endorses White's methods with a tale of her

death-bed healing by the White using them. This chapter delves into thicker

esoterica than previous chapters, with bizarre accounts of nerve

locations and theories of magnetic flow within the body, as well as

how to influence these centers with application of personal magnetic

power. The cures to general aches and pains—in the arms, legs,

eyes, back, liver, etc—are all covered, as well as more general

afflictions such as Rheumatism. The student is instructed to charge

between a $2 and $5 fee for these treatments once they learn White's

secrets. Most amusingly, the chapter ends with stout assurance to the

students: “You cannot fail.”

With

Series F, the book takes a turn toward classic astrology in its

“Spiritual Planetary Reading” chapter, which is reflective of one

of the Whites' earliest endeavors as “Planet Readers.” It begins

with more admonishment for others to not handle the student's course

book, and then moves into fairly standard astrological information,

in typical cold read fashion, of the 12 classic astrological signs in

2-page spreads, which is exactly 21 pages more information than

White's generic one-size-fits-all pregenerated responses provided to

those paying for his planet-reading services. Interestingly enough, many of the

readings promote the inner power of the subject, in a way that

encourages them to pursue its development by no other means than Dr.

White's very own correspondence courses. Theodore never misses a

chance at self-promotion. The chapter closes with Sagittarius, and

doesn't delve into how a student is meant to actually “read” a

subject beyond the rote memorization of the astrological facts

promoted in the lessons.

Series

G is the book's 7th

and final chapter, and is a purer reduction of true occult studies in

the classic amulet, charms, and spells fashion, opening appropriately

enough with a full-page spread of a witches' coven stirring a

cauldron, the spirits of the dead being called down from the clouds

above to do their bidding. This chapter is less focused than others,

and covers a wide arrange of materials in a smorgasbord of occult

training, including conjuring evil spirits from the Astral plane,

casting out devils (perhaps students shouldn't have been taught to summon them in the first

place?), and making the blind see again with clay and spittle. Each

lesson is labeled as either “White Art” or “Black Art,”

seemingly without discrimination, with some Black Art providing cures

and some White Art summoning demons. As in the first chapter, many

biblical references abound, as well as warnings of the pursuit of

Black Art.

Amulets

and charms make up a large part of the chapter, which mostly involve

various prayers to be written on parchment to compel spirits to

appear, remove “unnatural” diseases, prevent evil, and bring

luck. It should come as no surprise that these charms are, of course,

ineffective if not written on proper parchment, which was only

available through White, and claimed to be of the same type ancient

Rabbis used to write divorces on. Much was made of this in White's

trial when it was revealed his ancient Hebrew Rabbi Parchment was, in

fact, Hercules brand tracing paper. What is noteworthy is the length

of the written prayers, some taking up a half page or more. No doubt

the lengthy prayers took up more parchment, and the more parchment

they took up, and the short frequency of their general effectiveness

once written, led to more orders to keep up one's luck and the evil

spirits at bay. Superstition can be a funny, and profitable, thing.

The

charms continue for nearly 50 pages. There are charms to hang around a

newborn's neck, a puzzling amulet to “cause a woman to be

successful in confinement,” charms for college students, for love

and friendship, to prevent witchcraft (hey, wait a second!), and a

charm to make your master become your servant. There are charms to

placed around farms to induce the growth of crops, spells to prevent

wasting disease, charms to prevent accidents and protect miners, and

amulets to preserve love between a man and wife. Some invoke holy

names. Some promote the sale of Adam & Eve root (available from

White, naturally), and others to sell White's cauls—another

fraudulent artifact that came to light in the trials.

Bizarrely,

the final pages cover Swedish massage, with full instruction on

kneading the flesh of subjects to relieve pain. The book's final

page, of course, offers the course's diploma, and “exquisite piece

of art” that is claimed to be “considered one of the finest ever

issued from a College of Science.” We're thankful that a picture is

provided, and it does seem to have been in impressive specimen, and was described as such in court.

|

| The Red Book's back cover. |

In

conclusion, the Red Book is exactly what I expected. It is a fun

perusal, and a real window into the mish-mashed esotericism of the

day, at least according to White and the sources he claimed to find

in the Peabody library. It exhibits the same confidence and chutzpah I've come to expect from White after reading the transcripts of his time on the stand at trial. I hope to return to it at a later date with a more thorough analysis of its place inthe grander scheme of history. One would think it wouldn't take much

comparison to locate his primary inspirations if one knew where to

look, and it is humorous to see the text so sprinkled with warnings

to potential copyright violators when it seems so obvious that White

was assembling his lessons with the table scraps of other occultists while scouring through the Peabody.

From the research standpoint of a collector looking for clues to

confirm White's earlier or later talking board endeavors, the text

comes up short. Perhaps there is a buried reference to the Algomire

Magic Cabinet that a first pass didn't reveal, but I'm disappointed

to not see an ad for the item, though I suspect since by this book's

1905 publication date, White had moved on from that earlier endeavor and committed fully to his new, as the Algomire tagline

was dropped from his advertisements in 1903. I had held out hope that

the book would contain a picture or mentionof the item, or even illustrations

that may have shown up recycled on the later I-D-O PSY-CHO

I-D-E-O GRAPH, but

it came up short.

Comparison

of the approximately 20 spirit-vision symbols listed in the first lesson

with the 43 non-astrological symbols present on the I-D-O PSY-CHO

I-D-E-O GRAPH in the museumoftalkingboard.com's collection brings a

few promising results, but nothing conclusive given the universal

nature of the symbols. The owl symbolizes business matters in both.

The white dove denotes prosperity on the board and good news from

afar in the book. The bald eagle denotes losses in both, just as the

anchor symbolizes success and the snake deception. The ear of corn is

compelling and means abundance in the book and feasting on the board,

and the swords are present on both but with divergent meanings, just

as the red rose is “truthiness” on the board and “happy love”

in the lessons. We have a match on the evil eye but a mis-match on

the lily. But there are twice as many symbols on the board as

described in the book, and even then the lists don't match with what

the lessons provide. All in all, there are a few markers that give us

hope to further bolster our conclusion that the Baltimore and Los

Angeles Whites are the same man, but likewise ultimately inconclusive

given the dissimilarities. But I'm not sure we could have expected

much more given the 14-year gap and ultimate intention and divergent

purposes between the two.

So, there you have it. The Red Book of Dr. Theodore H. White! When the day comes that I have a scanner large enough to capture it all, you'll get a chance to learn its inner secrets for yourself. I even promise to magnetize each and every download to attune to your personal magnetism, for faster learning of superior knowledge!